Today, for Teatime Thoughts, we are discussing empathy, and our tea for the day is Waitrose’s Darjeeling black tea, with an intoxicating scent that will send you floating atop the rolling clouds over lush green Darjeeling hills.

This compels me to share this cute picture of my mother and me from 2019 in a heavenly tea estate in Darjeeling for two reasons: 1. It’s hard to drink Darjeeling tea and not reminisce over how beautiful Darjeeling is. 2. It’s hard to talk about empathy and what it means to me without talking about my mother.

My mother is the physical manifestation of love itself. She has an inhuman capacity to give and feel for others. In almost any situation in life, no matter how big or trivial, I have seen her make decisions based on empathy.

And knowingly or unknowingly, she has passed on at least some of these qualities to me. Yet, I have struggled to accept this quality in myself.

Empathy: The Good

You see, empathy in theory is great. Empathy is the ability to feel others’ pain (or any other feeling) as if it were your own.

People who have higher levels of empathy reportedly thrive better in society. According to Good Therapy, an online group of mental health experts, being empathetic is crucial for building positive relationships with your family, at work, or anywhere else.

On the other hand, if you lack empathy, it could be a sign of issues like antisocial personality disorder or narcissistic personality disorder. A study also found that people with genes linked to lower empathy are more likely to have autism.

Empathy generally promotes feelings of concern for our fellow humans in distress. It can make us great listeners. It often motivates us to help and care for others. Consequently, empathy is often considered a moral quality.

But empathy on its own can have many negative sides.

But before we delve into that, let’s learn a little more about empathy.

Empathy: The Science

Because of empathy’s association with concepts such as morality, it’s easy to think of empathy as abstract. However, empathy is very much a concrete phenomenon that occurs in our brains.

Scientists have discovered a group of neurons in the brain called mirror neurons. These neurons show increased firing activity, both when you perform a specific task and when you observe somebody else carry out the same task.

Our brains activate the same neural circuits as the person we’re observing, simulating a mirrored internal state.

In terms of empathy, this means that when we see a friend in pain, the associated mirror neurons begin firing. This activates our own neural circuits dealing with pain. Thus, we’re able to ‘feel’ (at least to some extent) what our friend is feeling.

The Two Types of Empathy

There are two kinds of empathy: 1) emotional empathy and 2) cognitive empathy. Emotional empathy is the type of empathy mentioned above. It is our ability to ‘feel’ what others are feeling.

On the other hand, cognitive empathy is a more intellectual trait. It uses critical thinking to ‘know’ what somebody is feeling. It also involves perspective-taking: making inferences about a person’s social role, their motivations, and their perception of the world.

Emotional and cognitive empathy are separate and are supported by different brain networks. However, there is evidence that the two regions overlap and interact to influence our behavior.

Is Empathy Heritable?

A group of researchers analyzed twin studies on empathy and found that emotional empathy is much more influenced by our genes, while cognitive empathy is more influenced by our environment.

Even more interestingly, brain regions supporting emotional empathy are active from infancy but stay more or less the same throughout life. On the other hand, cognitive empathy develops from early childhood and continues to develop through adulthood.

This means that we can feel others’ feelings even as a baby. But our ability to cognitively understand and analyze another person’s thoughts and beliefs behind said feelings grows as we grow to understand the world and the people in it better.

Why are some people more empathetic than others?

Different factors affect empathy. A study conducted by Varun Warrier and colleagues at the University of Cambridge, in collaboration with 23andMe, collected saliva samples from 46,000 people.

Genetics

The study found that at least 10% of the differences in empathy from person to person can be attributed to genetics.

Oxytocin

The OXTR gene, responsible for the oxytocin receptor, affects empathy. Oxytocin is often called the ‘love hormone’ since it’s important in forming relationships and is released during cuddling and sex.

Variations in the OXTR gene can impact trust and empathy. It is also linked to changes in cognitive empathy.

This is very interesting because there have been many studies that relate oxytocin levels with empathy. Some studies have found that increasing oxytocin levels can help increase empathy and build trust and stronger social interactions, especially among people with autism.

Katie Daughters and her team, from the University of Cardiff, studied neurological patients with low levels of oxytocin. These patients did significantly worse in empathy tests and were worse in recognizing facial expressions compared to people with normal levels of oxytocin.

Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor

The BDNF (Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor) gene helps with long-term memory and learning. Recent studies found that changes in the BDNF gene are linked to lower levels of empathy.

Sex

Warrier’s research team also found that women are generally more empathetic than men. Interestingly, the scientists couldn’t find any genetic differences related to empathy between men and women.

This suggests that the empathy gap might be because of non-genetic factors like social roles.

Environment

Since only 10% of empathy variation is found to be gene-related, a big contributor to empathy must be the environment.

A study with 494 Chinese children suggested that parenting styles can affect a child’s ability to empathize and be altruistic. Children are much more likely to express feelings of trust and empathy if they receive emotional warmth instead of rejection from their parents.

Why do we have empathy?

Now that we know what empathy is and how it works, let’s talk about why empathy even exists.

Evolutionary Need for Empathy

Empathy, like most of our traits, seems to have risen from evolutionary need. In his paper, The Evolution of Empathy, Dr. Armin Schulz states that empathy was needed for survival, both for the individual and for the ‘tribe’ or species as a whole.

Parents needed to have empathy as caregivers so they could be attuned to the needs of their offspring and could ensure their survival. Animals in a herd needed to ‘feel’ the emotional states of other herd members to know when to help, and in turn receive help.

Furthermore, animals that could ‘sense’ fear in nearby animals could run away from predators before even spotting them, again increasing their chances of living. The rise of empathy had little to do with altruism at all.

Modern Needs for Empathy

While the survival pressures that led to the evolution of empathy no longer exist today, empathy is still very much needed for us to function in society.

Being able to sense other people’s feelings helps us understand social cues and adjust our own behavior accordingly. Empathy also often makes us feel concerned for others and motivates us to help those in need. Thus, it’s very important to form healthy social bonds.

Does empathy only exist in humans?

As empathy developed through evolution, it exists in many species. A baby chimpanzee has been photographed hugging an adult distressed chimpanzee who was screaming after losing a fight.

In a 1964 study on rhesus monkeys at Northwestern University, the monkeys were given a lever. If they pulled the lever, they would get food, but it would also shock a neighboring monkey. One monkey, to avoid shocking his companion, stopped pulling the chain and starved himself for 12 days.

While empathy is considered to be a ‘human’ quality, there is evidence of empathy in several other species. However, perspective-taking (the ability to cognitively understand another person’s point of view) is unique to humans.

Empathy: The Bad

If empathy can make us care for others, it’s difficult to see how it could possibly be a bad thing. But interestingly, some of the things that make empathy good also make it bad.

Empathy bias

Empathy evolved to help us look out for people in our tribe. This means that we feel less empathy towards outsiders: people who don’t look like us and people whose problems we can’t relate to.

From an evolutionary standpoint, this makes sense. If an animal felt empathy for all its companions in the wild, that would make it a poor competitor, and it would never be able to catch and eat its prey. But because of this, empathy can often cause biases.

Social, cultural, racial, and religious differences, especially triggered by subconscious fears, can make us empathize more with people who are similar to us, thus creating an us vs. them tribal mindset. This can create polarization and animosity.

Enter wars and genocide. This point is hilariously made in this Rick and Morty episode.

Empathy can be used for manipulation

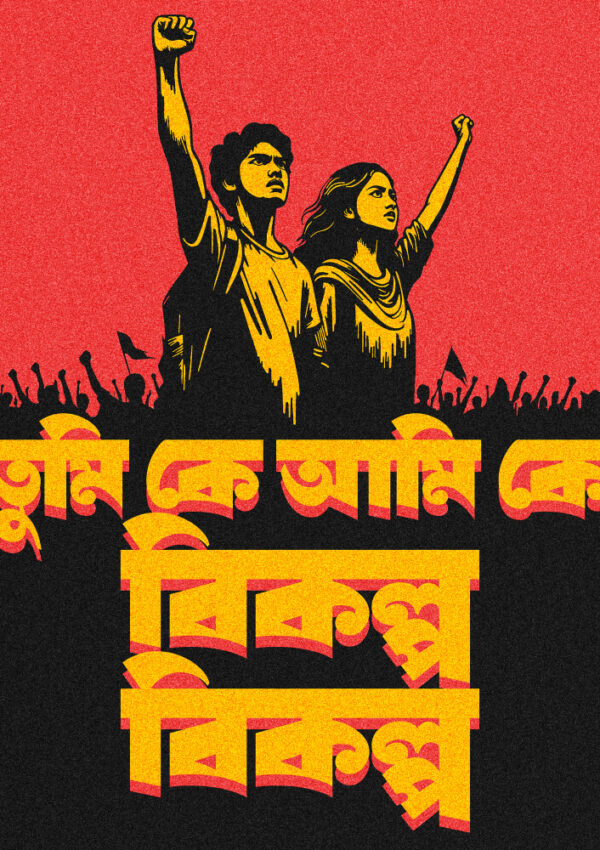

Politicians and activists often use empathy to manipulate the public, creating polarized us vs them narratives. This can lead to discrimination in all sectors and can even spark violence.

Fritz Breithaupt, author of The Dark Sides of Empathy, writes, “Sometimes we commit atrocities not out of a failure of empathy but rather as a direct consequence of successful, even overly successful, empathy.”

Humans naturally tend to take sides

When humans feel empathy for a certain group of people, they adopt the perspective of that group as their own. But the group on the other side of the conflict automatically becomes the ‘dark side,’ and we’re wired to distrust them as the enemy.

An example of this can be seen in the conflict in Northern Ireland. In the 2000s, some Irish schools tried to teach Catholic and Protestant youth empathy by introducing it into the curriculum.

They thought that learning about both sides would help them empathize with the other side and reduce conflict. However, results showed that the new generation was even more polarized, and schools had to abandon the project.

Our perception of pain limits our perception of others’ pain

In a study by Claus Lamm from the University of Vienna, people were given placebo painkiller pills that had a similar effect on the brain as an opioid, and then were given a shock.

Taking these pills not only reduced the pain the participants felt but also reduced empathy for the pain of other participants.

You can think about how men have no perception of the pain of childbirth, the same way that women can’t comprehend how it must feel for a man to be kicked in the gonads. It’s difficult for us to relate to the pain of others if our brains have no reference for that particular pain.

This becomes an even greater problem for things like climate change that require us to empathize with the problems of future generations who don’t even exist yet.

This means that we cannot rely on empathy alone to judge the severity of another person’s suffering.

Overcoming the bias of empathy using cognitive empathy

We must rely on cognitive empathy because of our natural tendency to have a more empathetic bias toward those who are like us. When emotional empathy is lacking due to differences like race, ethnicity, religion, or physical appearance, cognitive empathy becomes important.

Research shows that if we work on understanding others’ perspectives and care about the well-being of those who seem different from us, we can overcome these biases.

For instance, studies by Batson and his colleagues found that feeling empathy doesn’t always come from being similar or sharing feelings but can also come from valuing the welfare of people who seem dissimilar to us.

Question your biases

It’s important to constantly check your biases. This requires practice in introspection.

When our minds are already trained to quickly jump to pick a side, it will require a conscious effort in self-reflection, and we must ask ourselves some questions:

‘Why or how did I come to this conclusion? Is it based on evidence or emotion?’

‘Have I considered all the facts?’

‘What is the perspective of the person/group on the other side? What would I do if I were in their shoes?’

When you train your mind to question your thought processes, you will find that you can at least remove some bias from the equation.

Focus on what makes us alike

We are all much more similar than we are different. We may look different, talk differently, dress differently, or believe in different gods.

But at the end of the day, most of us just want to eat a few good meals a day and sleep in a safe bed. We want to spend time with our loved ones and feel loved and secure. And we want to feel heard and to feel like our needs matter.

In 2004, there was a big political controversy when the Israeli Minister of Justice, Yosef Lapid, expressed sympathy for the enemy. He questioned the Israeli army’s decision to destroy many Palestinian homes near the Egyptian border.

Lapid was moved by images he saw on the evening news, particularly a picture of an older woman searching for her medicines in the ruins of her home. He thought about how he would feel if it were his own grandmother in that situation. It’s important to note that Lapid’s grandmother had been a victim of the Holocaust.

If we remember to focus on the things that make us alike, we will find it much easier to empathize with people we are in conflict with.

Empathy without boundaries

Finally, let’s talk about how empathy can be incapacitating and personally harmful.

Philosopher Susanne Langer, when describing empathy, once said that it is an “involuntary breach of individual separateness”. When we feel the suffering of others, the lines between self and others can often become blurred.

This can quickly become exhausting. If you are constantly absorbing other people’s pain and over-identifying with it, it can lead to ‘empathic distress’. This can make it difficult for you to function in your own life and can affect your relationships negatively.

An overdose of empathy can also lead to ‘empathy fatigue’ or ‘empathy burnout’. “Such distress leads to apathy, withdrawal, and feelings of helplessness, and can even be bad for your health”, according to Dr. Singer and Dr. Klimecki, neuroscientists at the University of Geneva. About a third of medical doctors suffer from empathy burnout.

Compassionate empathy

You might think, ‘But children are starving and being bombed in some corner of the world every day. Are you saying I should turn away from their pain just because it makes me feel bad?’

But the thing is, ‘feeling’ can often be a barrier to ‘doing’. If we get too caught up in another person’s suffering, it can stop us from taking action that could actually help them. It can also eventually make us numb and apathetic, and want to withdraw from the source that’s causing us pain.

It’s important to sometimes step back from a situation to view it objectively and to think of possible solutions. Here comes a third type of empathy: compassion.

Compassion is essentially empathy coupled with action to relieve someone else’s suffering. The active aspect of compassion allows us to detach our emotional state from others and see ourselves as distinct individuals.

It’s not necessary for us to personally feel someone’s pain to assist them. Compassion is associated with activity in brain regions linked to positive emotions and actions. Experiencing compassion brings about a rewarding and positive emotional connection when we extend help to others.

My struggle with empathy

And finally, we come back to my relationship with empathy and my mother.

My mother’s empathetic nature makes her deeply absorb others’ problems to the extent that it negatively impacts her well-being. She often gives away more money than she has, leading to poor savings. I have seen her help people who have, in turn, exploited her.

As a result, I have always seen my mother’s empathy as a vulnerability and a weakness. And that is how I have viewed it in myself.

In most of my relationships with loved ones, I have found myself feeling more and as a result giving more. And while unconditional love sounds nice in books, it barely exists in real life.

It’s difficult to give without expecting some reciprocation. And without it, you can’t help feeling like you’re getting the short end of the stick.

When you feel things very intensely, and you are constantly paying attention to other people’s emotional needs, it’s confusing when other people around you, who are perhaps less empathetic, aren’t as attuned to your emotional needs.

And it becomes very easy to tie it to your self-worth. This has also negatively affected my relationships, as it puts an unfair burden on the other person.

I have also been affected by empathic distress and burnout. I have often felt absolutely paralyzed, heartbroken, and unable to think of anything else when I see pictures and videos of children being affected by war and famine.

Consequently, I have felt increasingly guilty for all my privileges, and I found myself thinking that I don’t deserve any of it. And I have felt positively baffled that other people around me weren’t reacting as strongly to other people’s misfortunes, and did not feel as personally responsible.

As a result, I have often felt isolated and alone. I felt powerless in a cruel, unjust world, and I found myself falling into spells of depression.

That is perhaps what has prompted me to research empathy and write this article. I have learned that I cannot change the way I feel and perceive things. So I must accept myself as I am. And I must accept the sufferings of others that are beyond my control.

Empathy needs to be practiced with compassion, not just towards others but also towards yourself. It took me a long time to realize that empathy is a gift and not a curse when empathy is exercised with boundaries.

Tea and Empathy

Finally, where does empathy fit into the world of tea? Tea means many things to many people. Tea holds religious value and ritualistic significance. But often, tea is a time to share.

Tea time is a space for conversation. Making somebody a cup of tea when they’re in distress is a way to let them know I am here to listen. Therefore, tea and empathy often go hand in hand.

I will leave you with two beautifully written articles:

The first is by Joshua Fletcher, who worked in palliative care. Joshua writes that making his patients tea really made a difference: ‘A cup of tea is symbolic of a wider sentiment; when we don’t have anything left to give, we can still make a cup of tea.’

The second is by Jenna Waters. Jenna echoes the same sentiment in her heartbreaking article about how her six and two-year-old children heal together as a family after her partner leaves them. Tea time is a ritual in their everyday lives where the children learn to acknowledge and express their feelings and listen to each other.

And the last words will be Dali Lama’s: “Love and compassion are necessities, not luxuries. Without them, humanity cannot survive.”

References:

- The evolution of empathy| Aalto DF

- The complexity of understanding others as the evolutionary origin of empathy and emotional contagion

- The Evolution of Empathy by Armin Schulz

- The Evolution of Empathy

- The Science of Empathy

- ‘I Feel Your Pain’: The Neuroscience of Empathy

- The Psychology of Emotional and Cognitive Empathy

- How much of our empathy is down to genes?

- Is Empathy Genetic or Acquired?

- Low oxytocin may lead to low empathy, study finds

- The genetic and environmental origins of emotional and cognitive empathy: Review and meta-analyses of twin studies

- An excess of empathy can be bad for your mental health

- The surprising downsides of empathy

- Does Empathy Have A Dark Side?

- The Dark Side of Empathy

Leave a Reply